Rina Cutler, Philadelphia’s deputy mayor for transportation found herself stuck in traffic one day in 2009. There’s only so much one can do in such a situation, and once the obligatory radio station switching, dashboard dusting, and finger examining is finished, scanning the landscape helps fill the time.

The scene from her car that morning was the parking garage at Philadelphia International Airport, which fronts I-95. Creeping along in traffic, the deputy mayor had what people call an “ah-ha moment.”

“We’ve been told this is the largest above-ground parking structure in the world,” says the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program’s Director of Communications Jenn McCreary. “And she’s looking at this big structure and it struck her that it would be nice, instead of looking at this wall of concrete, if people could see a beautiful piece of art.”

Three years later, that’s exactly what everyone from the highway admires. Thanks to a partnership between the Mural Arts Program and the city’s Office of Transportation and Utilities, the garage was wrapped with the world’s second-largest mural, depicting city residents dancing against a dramatic black background.

“We look at this art as a gateway to Philadelphia,” says McCreary. “You’re welcomed to the city from different points, and when you’re landing here, you’re greeted by this piece of art.”

It took two years to create the mural and four months to install it, and engaged professional and amateur dancers from the city and more than 1,000 volunteers who helped paint the art and participate in a massive dance party in the garage to dedicate it. It’s become a city landmark and something of a wonder in the art world, and is part of a larger trend of cities and municipalities welcoming garages as not only necessary for transportation, but also giant canvases to beautify the landscape.

How Philly Moves

McCreary says photographer Jacques-Jean Tiziou photographed nearly 175 dancers in everything from ballet tutus to traditional Native American robes. “We had professionals, amateurs, small children, grandmothers,” she says. “Over the course of about six weeks, he did photo shoots with all of them and then ultimately selected the images that appear on the mural.”

After that, a team of five professional muralists set up shop in vacant retail space that was donated to the project by the Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust. Over the course of nine months, the artists painted the 1,504 panels of parachute fabric that would become the final mural.

“We had community paint days, too,” says McCreary. The public was invited to visit the makeshift studio on several weekends to pick up their brushes and become part of the project, and more than 1,000 people took the city up on the offer and jumped in.

“People from the area and visitors to the area could come in and help paint the pieces,” she says. “They gridded out parts of it like a giant paint-by-number, and anybody could come down and dive in and feel like they were part of this iconic piece of art.”

After that, workers spent four months stretching the fabric and adhering it to the exterior walls of the garage, covering 85,000 square feet with the panels and sealing them with acrylic gel.

The airport happily jumped into the project as well, dedicating space inside to a permanent exhibition about the mural. There, visitors can watch videos about the making of the piece and see some of the photographs that didn’t make it into the final design.

“People love it,” says McCreary. “It’s something new. It’s something fun.”

Florida

Farther south, in Clearwater, Fla., city residents have for years identified a municipal parking garage by its exterior murals of birds.

“The garage sits across the street from the police station and the fire station headquarters,” says Christopher Hubbard, cultural affairs specialist for the city.

“It was constructed about 15 years ago, and there were windows built into it to fill with artwork. At the time, we were running an artist in residence program, and Roger

Bansemer was chosen to be the lead artist for that project.”

Bansemer created a dozen double-sided paintings of local birds on weather-treated pressurized boards, and those were installed into the garage’s windows. Since then, they’ve become a popular local landmark.

“We have wayfinding for downtown that was created when our downtown district went through a rehabilitation,” says Hubbard. “We wanted a new perspective on what our downtown should be, and we used the birds on our wayfinding map.” Today, he says, people identify the garage to visitors by its birds.

“The county bike trail runs right past the garage, and the birds have become an icon of that section of the trail,” he says. “That’s how people know they’re in Clearwater—they see the birds. If you talk to people about what they see downtown, they’ll tell you about the architecture and the artwork.”

The panels are flipped regularly so they weather evenly, and all of them were rehabilitated last year to bring them back to their original vibrancy.

Other Florida artists are also jumping into the fray. In December 2010, Fort Myers celebrated the dedication of its Parallel Park art project that encompasses 30,000 square feet on the Lee County Justice Center parking garage. Commissioned by Lee County and the City of Fort Myers through the city’s public art program, the series of Marylyn Dintenfass murals depicts geometric shapes on a huge scale, and was part of the city’s public art requirement for private developers.

“If developers build within Fort Myers limits, they have to comply with this public art ordinance,” says Florida Association of Public Art Professionals Board Member Barbara Hill, who spearheaded the project. “The architect thought if he brought in his in-house designer to put a pattern of some kind on panels on the garage, that would suffice as the public art component. I was the city’s public art consultant at the time, and I said no.”

She led a search for an artist and ultimately chose painter Dintenfass, who created her patterns on huge sheets of Kevlar material.

“We brought in a fine artist to work on what was supposed to be a simple design element,” says Hill. “It turned out to be so much more as a result.” To date, the piece has been the subject of a book and at least one exhibition, and was recognized by the Americans for the Arts annual public art awards.

Challenges

Those who’ve installed public art on parking garages say that while it’s worth the effort, transforming exterior concrete walls into something beautiful isn’t exactly simple.

“Kevlar withstands the elements beautifully, but it’s a mesh,” says Hill. “Half of the fabric isn’t there. You have to really saturate the fabric with ink to make a visual impact. We took what was originally specified by the architect and actually doubled the resolution.” The Kevlar was then coated with an archival material to protect the piece.

“One of the biggest things we talk about in the public art community is the lifespan of artwork,” says Hubbard. “No matter how you cut the pie, it’s art that’s outside. The paint will fade. Things will get scratched. You have to be very foresighted in the maintenance that you do.” His program sets aside 10 percent of the original cost of each piece of art for future maintenance, and still says, “No matter how much you put into it, this kind of piece will not last forever.”

“You can use materials that are incredibly durable and long-lasting,” says Hill. “Go into any major subway system. You’ll see art that was done almost 100 years ago.”

Her project’s Kevlar panels were possible because, she says, they were part of the original construction budget for the garage. That kind of planning makes public art installation easier.

“The dilemma of a lot of people who are not only building garages but other structures as well is that they can’t afford to hire an artist,” she says. “But if an architect and an artist are brought in at the very early design phase and able to collaborate, a lot of the materials the artist will use can be worked into the construction budget. It doesn’t cost a lot more than if you’re going to install a stucco wall.”

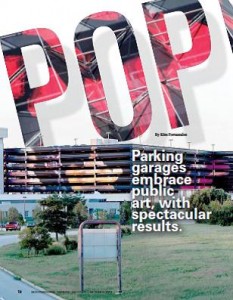

Some developers find creative ways around the cost. In Raleigh, N.C., delays on a new building that was supposed to wrap around the Convention Center parking garage left a stark concrete wall in the middle of the city. Developer Empire Properties solved the problem by asking design students at nearby North Carolina State University to enter submissions for art to temporarily cover the garage.

“We worked with the county to extend our development agreement,” says Empire spokesman Andrew Stewart. “In exchange, we agreed we’d pay for these banners to cover the parking deck.”

Thirty teams of students entered the competition, and “The Balloon Boys” were chosen to create massive banners with their fantasy illustration that incorporates mythical aquatic creatures with people and machines in flight over 20,000 square feet.

The final product has proven so popular that the county library system has jumped in, hosting a series of events for children about the murals. “The whole county is interacting with this,” says Stewart. “We wanted to have a piece of artwork that was suitable for adults, children, and families. The point was to solve a problem with the parking deck and give the area something really unique. Having this on that deck has become so much more.”

Other agree, and say the benefits to beautifying their garages go far beyond what they anticipated.

“A lot of parking garages are being done in fresh ways, both nationally and internationally,” says Hill. “When ours first went up with these beautiful colors that were so vivid, people kept going up to it thinking it was the city’s art museum. It looked for all the world like a museum, with this beautiful exterior, and they realized it was a parking garage. It’s pretty spectacular and we definitely transformed the environment.”

Kim Fernandez is editor of The Parking Professional. She can be reached at fernandez@parking.org or 540.371.7535.