The first purpose-built garage was constructed in Chicago in 1898. Again in Chicago, the earliest recorded multilevel parking garage was built in 1918. Less than a year later, as World War I came to a close, downtown Louisville, Ky., welcomed its first parking facility: the Morrissey Garage.

Originally called Bosler’s Fireproof Garage, the Morrissey Garage incorporated several sustainable and citizen-friendly initiatives that many parking garages fail to incorporate nearly a century later. For example, it had ground floor retail that over the decades has housed businesses such as a fruit market, bookstore, surgical supply store, Goodrich Tires store, and a garage equipment store. By providing space for these retail establishments, the garage helped reduce urban sprawl and negated the need to develop on previously undeveloped land.

The garage was designed to relate to the accompanying street and surrounding architecture, and its façade provided architectural continuity with the other buildings along Third Street. Unfortunately, many garages today in downtown Louisville—and elsewhere—display little architectural synonymy with their surrounding environment.

It also provided amenities such as vehicle detailing, polishing, and minor vehicle services that allowed drivers to accomplish such tasks without leaving the facility.

Having not parked a vehicle in decades, the Morrissey Garage now faces extinction and is currently boarded up to keep it from being an unattended homeless shelter. In 1983, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and it is now listed on the list of Preservation Louisville’s 10 most endangered places. When the time comes for its indubitable demise, Joni Mitchell may well sing about paving paradise by taking down a parking lot.

Louisville is home to another historic parking landmark as well: the Garage Experts Association of Louisville received a patent for the design for the Kehler Garage in the early 1920s. This garage was one of the first to incorporate continuous sloping design (both the ramps and the floor plates were sloped), minimizing the length and severity of the needed slope. Parking garages such as this followed in Detroit and Cleveland, and sloping floors are part of many garage designs used today.

Now

Parking garages in modern cities are sometimes considered eyesores that remind urban dwellers of our nation’s excessive dependency on the automobile. The City of Louisville, though, has made tremendous strides with its three most recent central business district garages.The Clay Commons Garage, Glassworks Garage, and First & Main Garage have all been erected in the past decade and have two things in common: technology and sustainability.

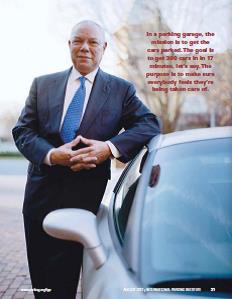

Operated by the Parking Authority of River City (PARC), all three garages use an automated cashiering system that allows users to pay on foot while walking back to their vehicles at the end of their time parked. This method helps eliminate vehicles idling to pay in the exit lane, thus limiting carbon emissions. The decision to go automated was not easy.

In the municipal world, where citizen approval means everything, would automation add to or take away from the customer service experience? Prior to implementation, PARC personnel visited numerous municipalities that had embraced parking automation to see if it would work in Louisville. They then implemented parking automation into one of their garages and studied the citizens’ ability to adapt to the technology. What they found is that parking automation may not work for every municipality, but it was a perfect fit for Louisville. After rolling out an effective marketing plan and signage package, they began transitioning cashiered garages to automated garages one at a time, using what they learned from each experience to improve the next. By implementing a state-of-the-art customer service command center, complete with audio intercom and visual cameras, and training ambassadors, maintenance, and security personnel on the new technology, they were able to keep their customer service standards high while decreasing vehicle entrance/exit times and improving ease and speed of payment.

Going Green

Environmentally-friendly features were incorporated as well. All three garages house bicycle racks that are available to the public, allowing safe, secure, and covered storage for cyclists and giving daily parkers the ability to bike the last mile to work. PARC is currently in the process of implementing more than 100 bicycle racks in all of its facilities, including 70 bicycle racks in one central garage that will be designated as a bicycle hub.

In 2005, Louisville Mayor Jerry Abramson held the city’s first bike summit and set a goal to become a gold-level bicycle friendly community by 2015, as defined by the League of American Bicyclists (LAB). The city reached the bronze level in 2007 and is currently working on the silver level. “Bicycling is important to Louisville city government administration, which is driven by the community; therefore it is important to PARC,” says David Gross, administrator of facility operations for PARC.

All three garages use smart lighting technology that’s equipped with a wireless control system to manage light performance through dimming, light sensing, and motion detection. This technology allows PARC to conserve energy and save money when the sun is bright and an abundance of lighting is not needed. Other advances include automated emails to PARC staff when a light is out or ballast is defective, and the ability to adjust light output through the lighting company’s user website.

PARC is also in the design stages of implementing a stormwater management system, complete with valves and cisterns to capture, store, and re-use rainwater for landscaping, irrigation, and other municipal needs. Depending on a demand study, PARC is considering implementing several electric vehicle charging stations that would allow drivers to charge their electric vehicles while parked in the facility. Several electric vehicle charging stations are currently being used daily in a University of Louisville campus parking garage just outside the central business district.

Design

Even with all these technological advances and sustainable initiatives, the city’s newer parking facilities are aesthetically pleasing. For example, the First & Main Garage was designed to match the architectural character of downtown Louisville’s Main Street. The then-mayor formed a committee to choose a garage design that best matched the character of the historic area. In the end, a company that specialized in historical preservation was chosen to design and construct this award-winning garage and indeed achieved the committee’s goal.

Transportation specialist Erik Weber estimates that at least one-third of Louisville’s downtown surface area is dedicated to parking. In a recent New York Times article, author Eran Ben-Joseph, Ph.D. estimated that in several other cities such as Orlando and Los Angeles, parking lots cover at least one-third of the surface area, making parking lots “one of the most salient landscape features of the built world” (see more from Dr. Ben-Joseph in the May issue of The Parking Professional).

The problem with this is that excessive and vast parking facilities contribute to the heat island effect, increase stormwater runoff, and encourage the use of single-occupancy vehicles. A recent study by Georgia Tech showed Louisville’s heat island to have grown more rapidly in the past half century than any other of the 49 cities studied, including Atlanta and Phoenix. The study did not cite the cause for Louisville’s rapid heat island rise, but abundant parking is sure to be one of them.

The bottom line is that Americans have a love affair with their cars. Just look at the fact that we almost spend more on the health and well-being of each vehicle ($2,536 per year) than on each family member ($2,747 per year). And the amount of money we spend each year on buying and financing each vehicle is three times the amount we spend educating each family member.

As people continue to drive downtown, whether in a Hummer or an electric vehicle, they will continue to need places to park. With any luck, parking operators such as PARC will continue to use technology and make sustainable decisions for the next 100 years of parking.

Isaiah Mouw, CAPP, LEED GA, works for Republic Parking System. He can be reached at imouw@republicparking.com.