The average parking facility operator or owner may be involved in one or two major purchases a year, while the average parking sales rep is involved in hundreds. At any given time, a sales rep could be involved in initial discussions with a potential customer, preparing a proposal, giving a presentation, or signing a contract for a new installation. During 12 years of parking sales experience, I have experienced the same sales cycle with all types of equipment and customers. I have witnessed the evolution of the industry from basic fee computers and gates to remotely monitored, fully-automated facilities. I have worked with many people to see their parking projects reach fruition.

Some of these projects have proceeded smoothly with barely a ripple of discontent, while others have been very challenging. The products and customers have changed over time, but certain principles are as relevant today as they were 12 years ago. The difference between success and failure comes down to a few core elements that continue to repeat themselves throughout the sales process.

The nature of parking sales—and sales in general—is that the job attracts people who are very driven toward success. There is no consolation prize for second. Request for proposal (RFP) awards are a zero sum game, which means that for every contract awarded, there are several losers. This is the nature of the game and every salesperson can spin a tale of saving an amazing deal from the jaws of defeat.

As a result of such intense competition, sales reps have developed a set of strategies that help us win our fair share of the business. We all pay our mortgages or feed our families on the deals we close, so we’re very adaptable. The variety of selling styles is as diverse as the number of personalities in sales. Some people are constantly pressing for the close; other people use a much softer approach. A reasonably experienced salesperson will develop a style that works well with most people they encounter.

The pressure of competition causes many salespeople to use specific tactics to gain an advantage. Anyone considering purchasing a parking system should be aware of some of the more common tactics that salespeople use to manipulate sales. Here’s your inside look and my tips to make the buying experience as positive as possible.

The Gimmick

The gimmick is a trick that salespeople use to convince a customer that a particular feature is absolutely essential to the success of the parking facility. Usually, the gimmick is a standard feature of the sales rep’s product, but either the competition does not have it, or it is a costly add-on. Sales reps usually try to weave these gimmicks into RFPs and bids to give them an advantage. The shelf life of a gimmick is usually about two years; after that, the competition adapts or the novelty wears off.

Most manufacturers produce competitive products that are equal to each other in important features and functions. Any feature that is truly useful will quickly be copied by others. Ask yourself how often you will use a feature and what it is really worth to you. You may find that the feature isn’t worth the cost to obtain it.

The 1 Percent Rule

Most manufacturers will guarantee that their product will work 99 percent of the time—this is the 1 percent rule. Sometimes this rule is revised downward to 95 percent reliability. The highest level of perfection that can be achieved by human engineering is 99.5 percent, or six-sigma. Unfortunately, nothing in the parking industry is manufactured to six-sigma standards, so the 1 percent rule is a reasonable measure of quality.

A 1 percent failure rate seems excellent by any standard; in school, a 99 percent score would be an A+. The problem for our purposes is that it skews the perception of time. If a parking manager had to deal with an equipment problem three times per year (or 1 percent of the time), it would not be a huge problem. Unfortunately, most parking manufacturers base their failure rate on the total number of transactions instead of time deployed. A ticket dispenser that works 99 percent of the time could still fail several times a week, depending on the number of people who have taken tickets. A busy garage could see as many as 10,000 transactions a day. Under the 1 percent rule, that means dealing with approximately 100 problems related to equipment failure or glitches every day.

Most customers underestimate the equipment failure rate for their garages and are surprised to see technicians and repair bills show up every other day. The customer should have a firm understanding of what 1 percent means: will they deal with three angry customers per day or per year?

Value Engineering

Value engineering is one of the most seductive traps in the parking industry, and occurs when a customer only has a budget to buy equipment up to a certain capability, but needs more power to achieve the desired results. The customer tries to achieve the desired result through a series of shortcuts or bending a product’s features to produce a benefit the product was never meant to deliver. The sales rep becomes sucked into this vortex, and nobody ends up happy.

I have never seen a value engineered project work to the satisfaction of the customer. Value engineering inevitably produces an abomination that will never function correctly and will sour the relationship between the customer and the sales rep. The sales rep will deliver a product that cannot possibly meet the customer’s expectation for performance, but meets the price point. Even if the customer acknowledges that the product was not designed to deliver the desired results, this is still a no-win situation. Several years down the road, no one will remember how much the equipment cost, but they will remember if it works to their expectation or not.

My advice to customers is to either pony up the money to get the features you need or delay the purchase until those funds become available. No matter how seductive or easy it appears, do not fall for the value engineering trap.

The Specification

The typical RFP is an ad hoc collection of 20-year old specifications that have been cut and pasted into a semi-coherent document. In many cases, the specification will actually contradict itself. The problem that most customers have in creating a specification is that they get too technical in an effort to impress bidders with their knowledge of parking equipment. Most specifications I read are so convoluted that I cannot actually provide a proposal based on the information given.

Most specifications are too specific in areas that are unimportant and vague in areas that are most important. A bidder wants to bid the minimum price given a level of risk or uncertainty. The more uncertain the specification, the more risk the bidder assumes. Risk translates into higher prices; the industry term for this is “fear money.”

A specification should be exact when it comes to quantities. If the quantity of ticket dispensers is not stated exactly, a sales rep will always assume the minimum. A specification should also state which features are absolutely necessary and not include any additional features. Many customers try to cover themselves by asking for every feature ever produced. Frequently, this ends up creating contradictions in the RFP and adds unnecessary costs. If you don’t need a fluorescent pink ticket dispenser that speaks 18 languages, don’t ask for it.

Civil work often leads to confusion. If the customer wants the civil work to be the responsibility of the equipment integrator, they must be able to answer very specific questions regarding conduit locations, sources of power, and internet availability. My recommendation to most customers is to leave the civil work out of the bid. There is too much uncertainty to bid this work on short notice, and if the equipment integrator is going to use a subcontractor, the customer ends up paying more.

Apples to Apples

Everyone wants a deal. Who wants to pay too much for too little? Most specifications and RFPs that I respond to have detailed technical sections that require the bidder to answer a series of questions that are specific to the needs of the garage. Most customers, though, do not read the technical specification and skip right to the price. Honestly, I could write the technical response in Swahili and no one would notice as long as the price was clearly defined.

Customers have an almost irresistible desire to compare vendors “apples to apples,” which means comparing price to price. If all parking vendors sold the same product and had the exact same level of local service, this would work well. Unfortunately, manufacturers and product integrators are very diverse in the level and quality of products they offer. A customer has to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of a vendor’s reputation against their price.

A fundamental question that is seldom asked is whether the vendor has technicians who are local to the area. Whatever product the customer buys, it will almost certainly break down at some point. Can the customer get local support in a reasonable amount of time, or does the call get forwarded to India where a technician will be dispatched next time they are in the country?

No one will remember what price they paid for a parking system three years after the purchase, but everyone will remember if the product and service meets their expectations.

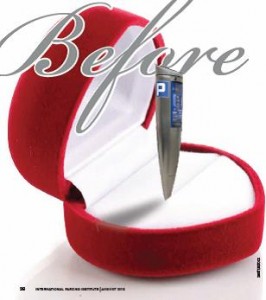

Buying a parking system is a daunting task, and in a lot of ways, it’s like getting married. Every system has its own individual idiosyncrasies and peculiarities that the buyer will be required to live with for the next 10 or more years. The cost of a wedding is about as an accurate a predictor of how long a marriage will survive as the initial cost of the parking equipment predicting how well it will work.

You are swimming with sharks who sell parking equipment every day. My advice to the many minnows making their first major parking purchase is to do your homework. Don’t allow anyone else to do it for you.

Brian Mitchell is senior account executive at Whitaker Parking Systems. He can be reached at bmitchell@whitakerbrothers.com or 301.873.7279.